In this research update, we’re taking a break from problematic random number generators to look at cryptocurrency wallets which are based on human-chosen passphrase strings. We outline what makes this wallet type such a bad idea and show some search results.

Table of Contents

Breaking Brainwallets

Introduction and Scope

For the purposes of our research, “brainwallets” are cryptocurrency wallets with a private key which is directly derived from some secret that a human selected without the help of a random number generator.

Humans are notoriously bad at picking high-entropy passphrases and remembering them to the letter over a long time span, which makes this underlying design a really risky foundation for storing any funds. Brainwallet variants that don’t add any unique cryptographic salt before hashing and use a very-quick-to-compute key derivation function (such as a single round of SHA-256) make this key generation scheme even worse, to the point of being horribly insecure. Arguably, it’s hard to design something even weaker for this purpose, though the bar for creatively bad password hashing is generally low (honorable mention: LM hash).

To put this into perspective: by creating wallets based on a single passphrase string, a fast hashing algorithm and nothing else, you’re essentially using the blockchain as one big shared password hash database that allows everyone to brute-force against all brainwallets of a given type at once, offline, in parallel, with no on-chain costs.

Which is the fun part for us 😎

Prior Research and Relevance

Let’s be clear: breaking brainwallets with weak generation patterns is an old hat. It has been studied and discussed widely for over a decade at this point. The simplicity of the involved derivation steps and variations (or lack thereof) is part of what of what makes it interesting, though.

A quick excerpt of relevant sources:

- Ryan Castellucci’s DC23 talk, slides, blogpost, brainflayer software - 2015

- The Bitcoin Brain Drain: Examining the Use and Abuse of Bitcoin Brain Wallets paper - 2016

- bitcointalk.org forum thread on 18.5k+ weak brainwallets - 2018+

Given the popular disclosure in 2015 and the better availability of more secure wallet generation alternatives around that time, we expect that most users stopped using brain wallets long ago. From our perspective, this makes weak brainwallet more or less a problem of the past, compared to the other and more recent wallet generation vulnerabilities we investigated, with some rare exceptions as outlined below.

To summarize, our research into the subject is overall more aimed at documenting the history of this well-known problem area and enjoying the relative simplicity of the research, than to present any fundamental new breakthroughs.

Data

Similar to our other work related to weak PRNGs, we’ve published a curated collection of discovered addresses from weak brainwallets to our Milk Sad research data repository. Take a look at brainwallet folder with the machine readable lists of affected wallet addresses, sorted by algorithms and coins. Common block explorers and other automated software can use this information to show transaction details.

Since the wallets in question do not have any hierarchical sub-wallets or sub-paths, there is exactly one private+public key pair per weak brainwallet passphrase and algorithm. Usually, this means that only one address is in use per coin, though there can be exceptions with multiple different Bitcoin address standards, for example.

At the moment, we’re not publishing a bulk list of discovered passphrases. Researchers interested in the raw passphrases should take a look at this list shared by phrutis, passphrases on privatekeys.pw, the previously linked bitcointalk forum thread, and other public sources that we used as a foundation. (Note that we do not endorse any sites or paid services.)

The additional wallets we found are all empty. This is unsurprising considering our limited search depth, the efforts apparently taken previously by others over the last years, and that we used publicly available data such as pre-existing wordlists and common derivations. Also note that since there are infinitely many possible passphrases, our search is not exhaustive, and represents a lower bound on what’s actually out there.

Snapshot of our current statistics:

| Hash type | Iterations | Coin | Number of addresses | Prior transaction volume | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SHA256 | 1 | BTC | 20397 | 3606.59 BTC | Well-known range |

| SHA256 | 1 | BCH | 19761 | Mostly due to BTC usage before the BCH hardfork | |

| SHA256 | 1 | ETH | 156 | ||

| SHA256 | 1 | LTC | 64 | ||

| ~ | |||||

| SHA256 | 2 | BTC | 75 | 51.28 BTC | |

| SHA256 | 2 | BCH | 4 | ||

| SHA256 | 2 | LTC | 2 |

In our results, SHA256(passphrase) and SHA256(SHA256(passphrase)) were the most common key derivation functions.

History

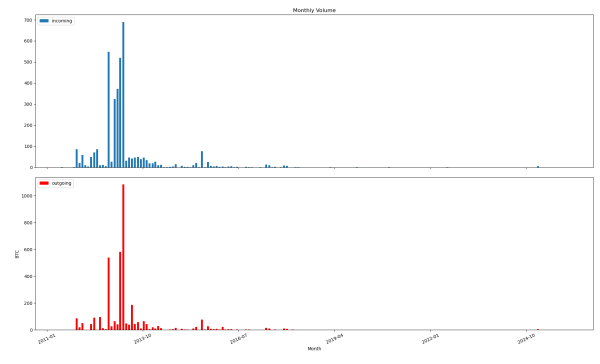

Here is a graph of the most active range, showing the prevalence of brainwallet usage in the early years of Bitcoin:

Most Recent Incident

The most recently seen weak high-value wallet in the 1-iteration-of-SHA256 range was bc1qskd34tec8fs04mmf0qzfjgq4e548ajc6ldqvex with about $500k USD (5.26 BTC) moving through it in February 2025. We can’t be sure that this money was automatically stolen by an attacker within seconds of the deposit, but it is very plausible to us. The password appeared in public weak password lists. Additionally, there is a public contact attempt to the new recipient address in transaction eb7ac22e..137a1764, asking the wallet “sweeper” to contact a @gmail.com address, which could be initiated by the victim:

1HeLLoSweeperPLeaseMaiLTo7784ibWK $0.53 bc1qxsge7nw8f9vskn7z3vmsdmwxjhwldvt5uytm22 $0.53 1DstoLen5AtGmaiLDotCom777777KcuU8 $0.53

Other Hashing Algorithms and Parameters

Our limited searches into wallets with other hash iteration counts for the key derivation didn’t reveal very much. There are a few results for 4x and 1000x SHA-256 iterations, respectively, but they are mostly dummy passphrases like hello.

Notably, we also found a few hits for keys derived via SHA3-256 that’s based on SHA3, unlike SHA256 which is based on the older SHA2.

| Hash type | Iterations | Coin | Number of wallets | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SHA3-256 | 1 | ETH | 4 |

New Code

We’re generally cautious when it comes to sharing our research code due to the inherent risk of misuse by black hats. However, for brainwallet related research, we think this ethical consideration is easier. Optimized brute force code for brainwallets has been widely available and replicated for over ten years at this point via brainflayer (context), with most new attacks likely leveraging GPUs and automated bots with pre-calculated results. In our view, this makes it acceptable to publish our research code since it doesn’t give attackers any meaningful new capabilities, while helping researchers to better understand and replicate edge cases.

You can find our CPU-based parallel brute force tooling in the rust-brainwallet-search folder of our Milk Sad code repository. It’s written in Rust and makes use of some other optimized code we outlined in our research updates previously.

This code finds weak private keys. We ask you to remember that with great power comes great responsibility, and also emphasize that this is unstable and unmaintained research code.

If other researchers want to get in touch about the published data or code, contact us here. (Please read the available code documentation beforehand, though.)

Research Note

A quick reminder that we have no involvement with any illegitimate withdrawal of funds from brainwallets. As researchers, we’re mainly trying to shine a light at prior weak wallet usage, hoping to help avoid future disasters through more public awareness of the dangerous software flaws that caused them.